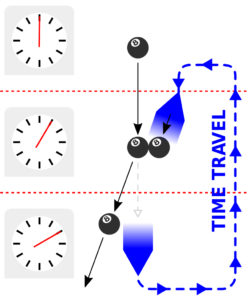

About the possibility of time traveling based on several specialized works, including those of Nicholas J. J. Smith (“Time Travel“), William Grey (”Troubles with Time Travel”), Ulrich Meyer (”Explaining causal loops”), Simon Keller and Michael Nelson (”Presentists should believe in time-travel”), Frank Arntzenius and Tim Maudlin (“Time Travel and Modern Physics“), and David Lewis (“The Paradoxes of Time Travel”). The article begins with an Introduction in which I make a short presentation of the time travel, and continues with a History of the concept of time travel, main physical aspects of time travel, including backward time travel in the past in general relativity and quantum physics, and time travel in the future, then a presentation of the Grandfather paradox that is approached in almost all specialized works, followed by a section dedicated to the Philosophy of time travel, and a section in which I analyze Causal loops for time travel. I finish my work with Conclusions, in which I sustain my personal opinions on the time travel, and the Bibliography on which the work is based.

About the possibility of time traveling based on several specialized works, including those of Nicholas J. J. Smith (“Time Travel“), William Grey (”Troubles with Time Travel”), Ulrich Meyer (”Explaining causal loops”), Simon Keller and Michael Nelson (”Presentists should believe in time-travel”), Frank Arntzenius and Tim Maudlin (“Time Travel and Modern Physics“), and David Lewis (“The Paradoxes of Time Travel”). The article begins with an Introduction in which I make a short presentation of the time travel, and continues with a History of the concept of time travel, main physical aspects of time travel, including backward time travel in the past in general relativity and quantum physics, and time travel in the future, then a presentation of the Grandfather paradox that is approached in almost all specialized works, followed by a section dedicated to the Philosophy of time travel, and a section in which I analyze Causal loops for time travel. I finish my work with Conclusions, in which I sustain my personal opinions on the time travel, and the Bibliography on which the work is based.

Keywords: time travel, grandfather paradox, causal loops, temporal paradoxes, causality

CONTENTS

Abstract

Introduction

History of the concept of time travel

Grandfather paradox

The philosophy of time travel

Causal loops

Conclusions

Bibliography

Notes

DOI: 10.13140/RG.2.2.17802.31680

MultiMedia Publishing: https://www.telework.ro/en/e-books/causal-loops-in-time-travel/